Background

A basic tenet of Wi-Fi marketing is to increase the number on the box to motivate buyers. But as savvy Wi-Fi buyers know, a Wi-Fi device can’t access link rates beyond the capability of its radio, which typically supports one or two streams. Yes, there is the occasional exception of 3×3 devices (MacBook Pro). But the overwhelming majority of Wi-Fi devices support at most two streams. For 802.11ac, this means they at most support 300 Mbps in 2.4 GHz and 867 Mbps in 5 GHz.

A key question SmallNetBuilder tries to help answer is whether "bigger number" routers will, in fact, improve Wi-Fi performance. With top-end products selling for $300 and up, real money is at stake.

We took the first step in this direction when we changed the standard test client from 3×3 to 2×2 in the Revision 9 test process, so that test results would present a more realistic view of performance that most users would experience. It also allowed fair comparison of test results across multiple product classes. But recent developments have prompted the next step in evolving SmallNetBuilder’s product research tools.

The current system of separating results by Wi-Fi class may be great for Wi-Fi marketers and retailers. But it doesn’t reflect the way people make product purchase decisions. But a greater motivation for change comes from the fact that the Wi-Fi "class" system is breaking down.

The current classification system has always combined the maximum link rate of both 2.4 and 5 GHz radios. This is the mechanism that adds the 300 Mbps maximum link rate (with 40 MHz bandwidth) in 2.4 GHz to the 867 Mbps maximum link rate in 5 GHz to equal 1167 Mbps, which is then rounded up to yield these products’ AC1200 class.

This system ignores the fact that a device can connect only to either the 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz radio for the sake of coming up with one simple number. But, while convenient, it set the stage for a numbers game that has confused and misled many Wi-Fi router buyers. Let’s examine the ways manufacturers have played the Wi-Fi class numbers game.

- 256 QAM: Originated by Broadcom, this took a standard 802.11ac modulation technique and incorporated it into 2.4 GHz 802.11n radios. But since it is a non-standard method in 802.11n, most device radios don’t support it and devices can’t achieve the number on the router box.

- "Tri-band" routers: These products damaged Wi-Fi class system credibility by adding in the maximum link rate of a second 5 GHz radio. This boosted class numbers to AC3200 for 3×3 designs, even though client radios still connect to only one radio at a time.

- 1024 QAM: Broadcom again led the way with a non-standard modulation technique, this time in 5 GHz. This allowed inflating dual-band 4×4 router classes from AC2600 to AC3150 and creating a new class of "tri-band" 4×4 routers that some dubbed AC5300 and others, AC5400. Do any devices besides routers support it? Nope.

- 802.11ad: Last year’s appearance of AD7200 class routers pushed class inflation to new heights by adding together the link rates of these routers’ 2.4 GHz 802.11n, 5 GHz 802.11ac and 60 GHz 802.11ad radios. Despite the much higher class number, most devices can’t even take advantage of these routers’ 4×4 n and 4×4 ac radios, let alone the 802.11ad radio, which requires a matching radio on the client side.

- 160 MHz bandwidth: This ill-considered part of the 802.11ac standard lets devices take up huge swaths, i.e. 8 channels, of the 5 GHz band to boost link rates without having to add more transmit / receive chains. Linksys has been the only one to take the bait so far, slapping an AC3200 class designation on its WRT3200ACM. But devices also need to support 160 MHz bandwidth and they don’t exist yet (and probably never will in 3×3 form). So we refused to play along and classed this 3×3 design as AC1900.

- "New math" classing: If classes can add together link rates of radios contained in one box, why not add together rates of multiple boxes? This logic has led Linksys (again) to class its Velop three pack of AC2200 mesh APs as AC6600. Words fail me…

- Class overlap: Take a "tri-band" design downmarket to a 2×2 platform and you end up with a class collision. AC2200 can now mean a 2×2 design with one 2.4 GHz and two 5 GHz radios that all support 256 QAM (400 + 867 + 867 = 2134). Or it can be an oddball combination of a 3×3 802.11n and 4×4 802.11ac 5 GHz radio which all don’t support 256 QAM link rates (450 + 1733 = 2183). Granted, the ZyXEL NBG6815 is the only example of the latter example. But with bandwidth, modulation rates, stream numbers, radio types and system architectures continuing to evolve, there are sure to be more.

SmallNetBuilder’s New Approach

In retrospect, the only-an-engineer-could-love approach we’ve taken has probably confused many first-time visitors to our Charts and Rankers in search of best-product recommendations. As noted above, it’s doubful buyers are looking for the best router within what amounts to an overly-contrived classification scheme. Buyers are more focused on best bang for the buck and whether trading up to a more expensive router will really deliver all the over-hyped performance promised in product literature.

So we’re making things much more simple by switching our Charts, Rankers and Finders to present Wi-Fi routers grouped by the following Types:

- Legacy – 802.11n and g products. This type is included so we can properly separate these lower performance products for ranking purposes. We don’t plan on reviewing any more of these products.

- Wired – Yes, routers without wireless radios still exist and need to be ranked separately.

- AC Router – All products with 802.11ac radios are included in this type. 802.11ad products are also included, as will 802.11ax when they appear, because they all will be primarily used with 802.11ac devices.

- AC DWS – This type includes multi-element "distributed" Wi-Fi systems, both "mesh" and router + satellite / extender types. These products are being grouped separately because product limitations prevent them from being tested under the same conditions as AC Routers.

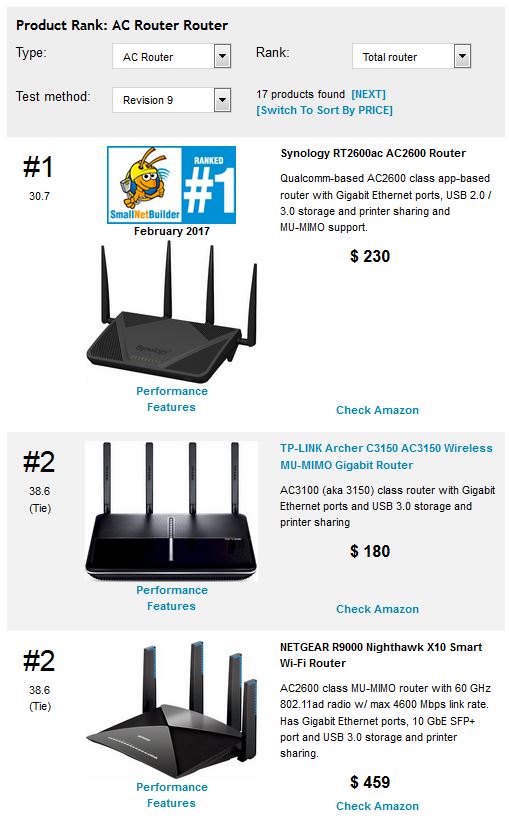

The most noticeable effect of this change is in the Router Ranker, which now ranks the performance of all AC routers in the same group. You have always been able to view benchmark results for all routers tested with a given test method in the Router Charts. Now you’ll be able to easily see how "bigger number" routers compare against their less expensive competitors using the Ranker.

Router Ranking by Type

For those still interested in router class, never fear. We’ll still cover all that with our usual attention to detail and teardowns in our product reviews. We just won’t let that information determine how we rank products. Due to the move from Classes to Types, we’ve also shut down the Router Search feature for now, since it was largely focused on router class.

Along with switching from class to product type based ranking, we’ve also tweaked the ranking criteria for products tested with the latest Revision 9 test method and renamed some benchmarks. We’ve renamed the maximum wireless throughput benchmarks to "Peak". So "Maximum 2.4 GHz downlink" becomes "Peak 2.4 GHz downlink". These benchmarks represent the maximum wireless throughput of a router when tested with a matching client. That’s why values for 4×4 routers (AC2600, AC3150, AC5300/5400) are generally higher than values for 3×3 (AC1900) and 2×2 (AC1200) products.

"Maximum" wireless throughput values in the Ranker for Revision 9 are now the maximum values found in the "profile" benchmarks. So 2.4 GHz Max. Downlink throughput would be equal to the values shown here. These "maximum" values better represent what most users will experience. The Router Ranker algorithm for products tested with the Revision 9 test method now also uses the new maximum throughput values.

We hope you like these changes. Please let us know either way using the SNBForums link below.