Introduction

What do you do for Internet access when you’re away from the office?

Internet access is essential for my home-based business, and I also frequently travel. Here are the methods I’ve tried when I’m on the road:

- Staying in hotels that provide Internet access and connecting only at night.

- Accessing Sprint PCS through my phone and a PCMCIA access card.

- Looking up free wireless hotspots online and using them.

- Paid Wi-Fi access at bookstores, coffee shops, and airports.

The only available option I haven’t tried that I’m aware of is Clearwire wireless broadband, which is available to me since I live in Boise, Idaho. Unfortunately, its area of coverage was too small to be a real alternative, since I worked with too many clients that lived in states that weren’t within the Clearwire service area. If you want information about Clearwire’s coverage areas in the United States, check their Interactive Coverage Map.

What doesn’t work? The four approaches I’ve listed above. This article will describe my experiences with the four approaches so that you can see why I feel that they don’t work. I’ll also describe my switch to Verizon Wireless’ broadband wireless service.

Options, but no Solutions

In my experience, I have found hotel-based Net access (Option 1) to be of uneven quality and getting worse as more people master the fine art of connecting to wireless LANs. Hotel staff are unaware of the poor speed and can’t do anything about it even when they are told. And in my case, accessing email just once a day is not being responsive enough to my clients.

Sprint PCS (Option 2) was the second solution I tried, and the whole experience was crazy. I tried Sprint PCS two ways: with a phone tethered to my laptop with a USB cable; and, via a PCMCIA card-based service. The whole experience was so frustrating and, at times, unbelievable, that it deserves its own section where I can rant without derailing the rest of this article.

The upshot of my experiences with Sprint PCS was that I found it to be unacceptable for on-the-road Internet access. Even the simple low-speed 56K Internet access that they could provide through tethered phones wasn’t something they wanted to provide, and their PCMCIA service—which was not any faster but had much better measured access—was too expensive for small business people like me.

Free Internet hotspots (Option 3) was the next solution I tried. At first, free hotspots seemed promising. The theory was that if you were attending a meeting in another town, you could stop by a coffee shop to check your email. Great theory, but not practical for me. I get lost in strange cities. Unnecessary driving can tip the scale away from the "almost missed" appointments toward possible disaster. Therefore, free access points are only an option for me if they happen to appear in places where I am already. Of course, in most places I find myself, I don’t have access.

The fourth Internet access method I have tried is what I think of as "Air Coffee." I actually prefer the pay-for-use Wi-Fi service at coffee shops, hotels, and airports than other services. I like a charge that is high enough to keep the bandwidth-hoarding riffraff off the network, but not so high that I would avoid paying. Typically, I have paid from $4 to $10 per access. Although last summer, I paid around $13 —more than my typical price—at the Narita International Airport when my flight out was canceled. But generally, the price I pay most frequently is $4.

Pay-for-use wireless services are a mixed bag of bad and good. In the category of "bad" pay-for-use services is T-Mobile. I was able to use it once, but haven’t been able to use it again because my first pay-for-use time somehow broke the login feature. I could probably fix the problem, but I can’t bring myself to call T-Mobile, wait as I’m put on hold, and then troubleshoot as if I were a T-mobile customer (prisoner). I’m not a T-mobile customer; I just want to access the Net.

Figure 1 shows the T-Mobile Hotspot Login available at Starbucks Coffee. The username and password fields located in the upper right-hand area are the key to T-Mobile’s user model. Using these, you will log in to the wireless access that you are paying for as a separate monthly recurring network communications fee. No shoes, no shirt, no login,… no service.

Figure 1: T-Mobile Log in at Starbucks

T-Mobile makes it easy to sign up for a monthly access program, but they make it difficult to buy one-time access. Because T-Mobile has made one-time access hard to buy, I follow an "anyone but T-Mobile" rule. At the Burbank Airport, for example, you can choose AT&T or T-Mobile—I always choose AT&T.

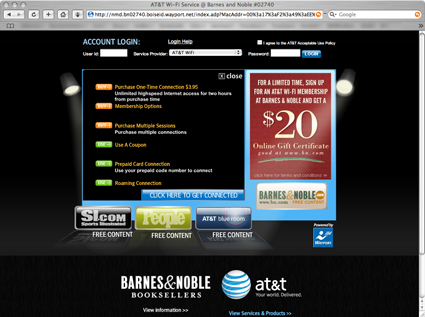

Why? Because AT&T is my favorite "good" pay-for-use wireless service. At my local Barnes & Noble bookstore, AT&T access costs $4 for two hours. This is fair. In fact, it’s great because $4 will keep the network-hogging riffraff off my connection, and I don’t work for more than two hours at a time at Barnes & Noble! I usually slip into the store to grab a coffee and my email; then, I’m off.

Figure 2: Log in to Air Coffee

The key reason I like AT&T access, however, is that they makes it just as easy to buy one-time access as they make buying a monthly subscription. Figure 2 shows that AT&T has User and Password fields to log in like T-Mobile. The difference between AT&T and T-Mobile is that on AT&T’s Web page, you can click the CLICK HERE TO GET CONNECTED option, shown in Figure 2 (located below the hand holding the book in the main image).

Figure 3 shows the screen that will appear where you can choose Purchase One Time Connection from the payment plans listed.

Figure 3: AT&T’s Most Excellent 1-Time Access Option

When you click Purchase One Time Connection, you are taken through a very slick, very simple purchase payment process, and your access is turned on. The process takes about a minute. I had been very happy to pay at the coffee shop for two years… while waiting for my Sprint PCS contract to expire. When paying for Wi-Fi access, I say to myself, "Gee, $4 for 2 hours is a lot, as in, a lot less than Sprint PCS and a lot less that $500 bill!" Then, I smile and type in my credit card number.

A Miracle Occurs

"Air Coffee" worked until this past December when I left Sprint PCS for Verizon Wireless. Why Verizon Wireless? First, because a report on cellular companies in a leading consumer publication consistently appeared to say, "All cell phone companies are bad, but Verizon is 6% less bad than the others."

Also, in the 2 years I’ve been on Sprint PCS, the Verizon wireless broadband (EVDO) network had expanded to cover the few places I needed access to that previously only Sprint had covered (Traverse City, Michigan being the most important for me). Finally, because the rest of my family was on Verizon Wireless. So, Verizon it was!

After "The Great Sprint Debacle", I had resigned myself to always using pay-for-use coffee shop wireless. However, David Pogue’s New York Times review of the Palm Treo 700p last spring (May’s Treo Leapfrongs past January’s) lit a candle. As I read the review, I felt a tectonic plate shift under me.

But even though I saw that Sprint had turned on EVDO access where I am in Boise, Idaho, I couldn’t move from my old phone to a Treo 700p on Sprint. Although I actually did consider moving to a Treo 700p on Sprint at one point. But whenever I ran the scenario over in my head of actually doing it, I got hung up at the part where I explain to my wife how great it was going to be.

See, I had told my wife all about how great Sprint PCS was going to be before I had signed up. She gave me "the look," which translated to "you’re a hopeless wannabe geek that knows this is too good to be true" and, of course, she was right. When, subsequently, Sprint PCS trampled over me, they also trampled over future upgrades and any possibility of staying with their service. As I always said, "once burned, wife-shy."

But then a miracle happened. Being a wannabe geek, I promptly disregarded all that I’ve learned from the "Great Sprint Debacle" when my wife and I stepped into a Verizon Wireless store in December.

Me: "How much per month for EVDO access?"

Verizon salesperson: "$40 and you can turn the service off in the months you don’t need it."

Me: "Can my laptop access the Internet via the 700p?"

Verizon salesperson: "Yeah, you can do that."

I sneaked a peek at Wifey, who remained calm. She didn’t say, "Don’t even think about it!"

So I thought about Internet access via a Treo 700p. Specifically, I thought about giving my laptop Internet access through a Treo 700p. Clearly, the salesperson had never done it. Although she was a fantastic help on the telephone aspects of the Treo 700p—she could finish my sentences for any questions about a phone-related issue—she couldn’t tell me how to set up my laptop and phone to work together.

But that didn’t matter! The "thing" that mattered the most was that Verizon didn’t tell me that I shouldn’t use my phone as a modem, which was a big step up from my Sprint PCS experience!

OK, I was in. I bought the Treo 700p and a belt clip holster, and I committed myself to two more years of cell company servitude. I was on my way.

The video version of David Pogue’s column (accessible from the article linked above) showed a laptop accessing the Internet over Bluetooth and EVDO. Check out the video at 1:32 into the 2:07 minute video. You’ll see a laptop accessing the Internet while the Treo 700p rests in Pogue’s right-front jean pocket. How did he do that?

In Part 2 of this series, I will show you how to reverse-engineer David Pogue’s setup. Yes, a wannabe geek actually got this to work. In the meantime, if you’re itching to find out about the Treo 700p and Internet access right now, check out EVDOinfo.com, EVDOforums.com, and Booster-Antenna.com.

By the way, we can all benefit from sharing notes on what works. So please share what has worked for you by posting a comment. Do you have a better way to access the Internet than the ways I’ve tried? If you’re a Clearwire fan, let us know. If you use tachyon beams, radar, or some other true hardcore geek access technology, please, please let us know, too.

Sidebar: TGSD or ‘The Great Sprint Debacle’

I signed up for a Sprint PCS phone after going to a retail Sprint store and asking if it were possible to access the Internet using a Sprint phone. The salesperson said, "Yes," and sold me a cable, a phone, and a Sprint PCS plan. Then, I went to the Sprint PCS Web site and downloaded Sprint’s software for using phones as tethered modems. It was F-A-N-T-A-S-T-I-C!!!

Fantastic… except that Sprint’s policy in 2003-2004 was not to allow customers to use their phones as modems! Alas, I didn’t learn about this gotcha until months later after I had started using their service. The way this happened is that as I told business associates and friends about Sprint’s ability to provide Internet access via phones, they would sign up with Sprint and start using their phones to access the Internet.

After a couple months, friends started calling me to warn me that Sprint didn’t want customers to use the phone to dial into the Internet. My friends were finding $100 charges on their monthly Sprint PCS statements and when they called Sprint, customer service told them they weren’t allowed to access the Internet with their phones. If the customer persisted in escalating this nonsense to a customer service supervisor, the charges were backed off their statements, but they were warned again not to use their phones as modems.

Oddly, the Internet access charges didn’t appear every month on my friends’ statements. And the charges never appeared on my statements, even though I had some months where I used the service extensively.

In hindsight, it felt as if a human were running a database query every so often perhaps as a capricious boss demanded it. When so commanded, he or she dipped into the ocean of packets to see if there were any "packet criminals" using their phones as modems. I came to call the random Sprint charges, "The Sprint PCS Random Internet Penalty Charges" (SPCSRIPC).

When I heard from my friends about the SPCSRIPC six months into my two-year contract, I went straight to my nearest Sprint PCS company-owned store. "You’re charging penalties to access the Internet with your phones," I said. "What is going on?"

Sprint salespeople: "You can’t do that!"

I then demonstrated on the spot how, in fact, I could do that.

Sprint salespeople: "You’re not supposed to do that!"

Me: "Why?"

Sprint salespeople: "Because… just because we’re told not to let customers do that."

If you have teenagers, you probably have experienced telling them to stop doing something because of your own vague sense of unease. When they pushed back, you caught yourself not really having a good reason to tell them for not doing whatever it was they were doing. This is called "jerking your kid around." Sprint PCS was jerking me around, and I was in the position of the frustrated teenager.

The company-owned store personnel would say haughtily, "Oh yes, you must have signed up with a Sprint PCS franchisee. They are selling things they shouldn’t."

Selling things they shouldn’t? Defining things that should and should not happen is what contracts are for. Their contracts are probably downright draconian, spelling out completely what is OK and what is not OK for the franchisees to sell.

My guess is that the problem was not extra-contractual behavior. The problem was that Sprint PCS had not seen what was going to happen when it set up the contracts and when it built its infrastructure. Something simple like a "packet distintermediation" took place.

- Sprints contracts were set up assuming all high-bandwidth users would use PCMCIA cards.

- The infrastructure was put in place to meter all the PCMCIA packets.

- Then a decision was made that phones could be allowed to provide access.

- Then, the assumption was made that phone users would never use more than trivial amounts of network bandwidth.

- A decision was made not to meter the tethered phone connections to the Internet.

When phones started disintermediating the packets that Sprint assumed would only flow through PCMCIA cards, the corporate weenies folks did not like what was happening. But it was too late. The contracts were already in place.

Obvious questions that Sprint PCS wouldn’t answer were:

- Why does Sprint PCS’s network allow me to dial in with my phone if they have a policy against it?

- Why are tethered phone users not charged every month they use the phone as a modem?

- Why is the enabling software for Internet access made available for free on the Sprint Web site if it is against Sprint’s policy to let customers have tethered phone Internet access?

- Are the "engi-nerds" at Sprint PCS at war with the "marketeers"? Providing the technical services that customers need in spite of the complaints and whining of marketing speaks volumes about a cultural conflict.

But, for me, it got better. Once I realized that Sprint PCS really really didn’t want me to use my phone as a modem, I looked around for alternatives without a "worry tax." The worry tax was a "psychic" tax I began paying after I learned Sprint didn’t want me to access the Internet with my phone, but when I did it anyway. I was terrified that a secret Trapdoor of Destruction was going to spring open and the Sprint PCS Random Internet Penalty Charges would wreck havoc on my Sprint PCS account.

The next best thing to a USB-tethered phone was the Sprint PCS PCMCIA-based data card service. Where the USB-tethered phone was discouraged, the PCMCIA seemed to be encouraged by Sprint. So, I signed up. The deal, the Sprint PCS on-the-phone salespeople told me, was that the PCMCIA-based service came with a two-month guarantee of no charges over $80 so that I could figure out which sized plan I needed. The PCMCIA card-based service as I recall was "fast, fast, fast!" But actually, I think it was the same speed as the tethered phone.

So guess what my bill was at the end of the first month? Of course, it was $500 for 150 megabytes of traffic!

When I called Sprint PCS customer service, I learned that they didn’t know about the Sprint PCS salesperson’s "no charges over $80 a month for the first 3 months" guarantee. Suddenly I felt like a chicken trampled over by an elephant.

Some people love this kind of situation (see Consumerist’s Verizon Doesn’t Know How To Count). But, not me. For me, the big lesson is that cellular sales advice and what actually happens after you’ve signed the contract are positively correlated. That is, unless you have geeky needs. In that case, the more geeky your needs, the lower the correlation. With some key features such as Sprint PCS’ guarantee of "no charges over $80 for the first 3 months," the correlation may be zero.

The worst thing about dealing with giant bureaucracies providing wireless technologies is that they are like elephants dancing among chickens. Once again, post a comment, or drop us a line if you have an experience to share. Posting our experiences of being stepped on might help us "chickens" help each other avoid being crushed!

Next time in Part 2, I’ll give you a detailed how to for getting a Mac and Treo 700p connected via Bluetooth and on the Internet using Verizon’s BroadbandAccess EVDO service. See you then!