Introduction

Updated 31 March 2005

It’s the third or fourth hour of the flight that the lassitude sets in. You’ve been fed (meagerly), read part of a book, flipped through the in-flight magazine, and watched part of a movie that you didn’t want to see on the ground. Now what do you do for the next two, three – or 10 hours?

Connexion by Boeing wants to turn your on-plane boredom and downtime into productive time by pumping in a high-speed broadband Internet connection via satellite. The Connexion service has been in the works for years, and almost faltered after September 11 caused a downturn in domestic U.S. airline sustainability and worldwide business activity.

However, the division retooled its efforts, refocused on long-haul flights, and has brought an Internet service to market that, so far, appears to deliver on its promise based on a test flight that I took in the Seattle, Washington area, and on the experiences of several travelers, including one of Toms’ own editors.

Figure 1: Surfing the Net at 30,000 feet

(click image to enlarge)

The service is so far live on certain planes and routes from Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines, SAS, ANA, and Japan Airlines, with China Airlines, El Al, and Korean Air coming this year. British Airways has signed a letter of intent but has no timeline on adding service. Lufthansa has Connexion reliably on about 13 cities in North American to and from Germany, while SAS has committed to Connexion on all flights to and from Seattle.

Connexion, through its airline partners, offers both flat rate and pay-as-you-go plans. Flights of less than three hours cost $14.95 for unlimited use; three to six hours, $19.95; and more than six hours, $29.95. The pay-as-you-go option offers 30 minutes for $9.95 and 25 cents per minute thereafter. While the per-minute rate is steep, for those who need relatively little access during a long flight, paying $10 to $15 for 30 to 50 minutes of access might make more sense than ponying up $30 for unlimited access. Most business travelers, however, will simply pay for unlimited access.

For one-off uses, you sign up through a connection screen that’s just like those used in terrestrial hotspots. Credit card information is secured via an SSL connection.

Going the Long Way Round

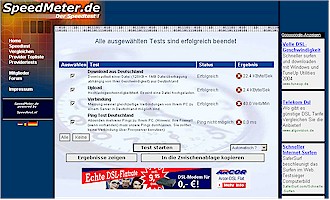

Connexion makes use of geostationary Ku-band satellites that can relay data from ground stations to fixed and moving receivers across geographic areas of a few hundred square miles. Satellites contain multiple transponder pairs – separated by receive and transmit – which cover a given region. The Ku-band is 10.7 to 12.75 gigahertz (GHz) which allows for an extremely high data broadcast rate.

There are several dozen Ku-band satellites operated by a number of different companies over the U.S. and around the world. Boeing has contracts with different satellite operators and the option to purchase more service as necessary.

“The solution was to use a frequency of satellites that had enough throughput to give people in aircraft an experience similar to that on ground,” said Stan Deal, Vice President, Commercial Aviation Business for Connexion by Boeing. Rather than invent new technology, Deal said, Connexion decided to put together a “business case around a set of existing technology to bring this into the market efficiently.”

The engineering challenge was to build a system that could handle airplanes traveling at 600 miles per hour at various latitudes and elevations that would allow the simultaneous broadband use by dozens of passengers.

Figure 2: How Connexion Works

(image courtesy of Boeing)

(click image to enlarge)

The technical and financial key to making Connexion work is the antenna used for satellite communications. “The antenna on the airplane is really the conduit inside and outside the airplane to the satellite,” said Deal. “It’s designed to be as efficient as possible in transacting signal to and from the satellite.”

The more efficient it is, the less cost to Boeing, and the more capacity that’s available. Deal noted that the best antenna would be the largest one, but “it’s gotta fly.” And the same antenna design had to work on planes that scale from a Boeing 737 up to an Airbus A380. (In fact, most of the early Connexion deployments have been on Airbus planes.)

The solution was to design an antenna that can track satellite positions, which allows Connexion to use the smallest possible footprint. On-board avionics already in use for flight information track a plane’s absolute global position, which is then handed off to the Connexion system to correlate against a table of known geostationary satellites. The antenna is constantly tracked against the optimum satellite, with changeover automatically handled by the on-board system.

“That allows us to essentially have aircraft equipped to look at these satellites that are parked above the equator at 23,000 miles above the earth and have coverage up to 75 degrees” north and south latitude, Deal said, which he estimates is about 99.2 percent of all air traffic. “There are a few aircraft – and there are coming more over time – that are starting to fly over the poles,” he noted, which would not be able to offer the service.

Access is supposed to be available throughout a flight. But reports from passengers indicate that while it’s generally reliable, there can be moments of disruption. However, those moments don’t last long if they occur at all.

Deal wouldn’t comment on reports last year that retrofitting a plane for Connexion could take as long as 20 days. However, in a publicity flight over Washington State in November 2004, Deal said that Connexion had recently reduced installation time from 10 days to under seven days. Seven days is a typical window for routine major maintenance intervals on commercial aircraft.

The planes use their swiveling antennas to talk to the satellite which in turn maintain fixed communications with ground stations. Boeing currently has stations in Littleton, Colorado; Japan; Lake Switzerland; and Moscow. A fifth hasn’t been announced, but will be up and running in April.

The raw speed delivered to the planes through this arrangement is rated at 5 megabits per second (Mbps) downstream (ground-to-satellite-to-plane) and 1 Mbps upstream (plane-to-satellite-to-ground). Deal said that the service can deliver up to 20 Mbps to a single plane, but no airline had yet requested more than 5 Mbps.

Connexion’s partner airlines have mostly chosen to use only Wi-Fi to distribute access throughout a plane. A few planes may be equipped with Ethernet jacks, such as certain Lufthansa models, but only in business and first class. (That’s where power jacks are located, too, on planes that have them.)

As we’ll see from real-world experiences, however, these theoretical maximums govern a plane’s overall bandwidth, and not what each user will see.

Is it really Broadband?

The technology may be fascinating enough, but it’s applications that matter – can Connexion be used for streaming audio and video and voice-over-IP (VoIP) calls? The answer appears to be pretty clearly yes.

Although Boeing won’t talk about exactly how it provisions bandwidth on each plane for each airline, Patrick Schmid, a senior editor for our sister publication TomsHardware, said that a flight attendant told him that there was load balancing among users involved in keeping service reliable.

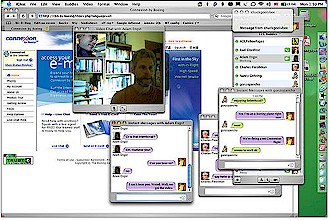

This is confirmed by his and other people’s experience. Schmid was able to see fairly consistent performance of 20 kiloBytes per second (about 200 kbps) downstream and 5 to 10 kB/s upstream (about 50 to 100 kbps) (Figure 3). “You can surf all the Web sites at a speed that is between ISDN and slow DSL,” he said after flying recently from Los Angeles to Munich.

Figure 3: Speed Test Results

(click image to enlarge)

Martyn Levy, vice president of business development at New Zealand-based RoamAD, tested throughput on a recent flight from Frankfurt to Singapore. He saw nearly 200 kbps downstream a well.

While this throughput seems ok for surfing the Web and checking email, latency could be a problem for users seeking to use voice messaging or VoIP services. Schmid also ran some ping tests during his recent flight and averaged around 900 msec to one website and 700 msec or so to another. Ping times varied, however, from a minimum of 600 msec to occasionally over 3 seconds. Keep in mind that these numbers include both the delay in the on-board wireless LAN as well as plane-to-satellite and satellite-to-ground legs.

Despite these less-than-stellar response times, early adopters like Schmid, Levy, and Alexander have used Skype for voice and found it acceptable. Levy said, “Skype voice worked fine provided you did not talk over each other.” Schmid noted that both Skype-to-Skype and SkypeOut calls to the switched telephone network worked for him, although a noise-canceling USB headset is highly recommended. I tested one during a demonstration flight that worked beautifully.

Video is also an option even at the limited speeds. Schmid saw a passenger next to him using a Web cam, and I was able to get streaming video working via Apple’s iChat AV in both directions (Figure 4) during a domestic Connexion demonstration flight that had one-fifth the bandwidth of a normal flight.

Figure 4: iChat Session

(click image to enlarge)

The biggest problem that passengers have reported is battery life on their laptops, which may make handhelds a more comfortable and reliable in-flight option for those outside of powered business-class/first-class seats. On a 14-hour flight, even two batteries might not last for the amount of work that could be carried out.

Not just for Passengers

While Connexion and its passengers are focusing on the routine uses of in-flight Internet access, Boeing’s Deal said that there are plenty of other purposes to which airlines intend to put the Connexion connection. For example, live broadcast video is coming later this year on Singapore Airlines. Initially, Connexion will offer four channels of news and information, but will expand into other programming, notably sports.

Crew use is also an option depending on the airline. “We’d like to encourage it because we like early adopters,” Deal said, but each airline has its own policies. However, it’s clear from talking to Connexion users that Lufthansa allows its crew at least some access because of their enthusiasm for the service.

Telemedicine is also expected to be an important use of the live Internet feed allowing a remote doctor to help diagnose passenger distress through video and biometrics – such as pulse and blood pressure – and either provide instructions or suggest an emergency landing. Right now, airlines rely on ground medical services to advise, but without access to the patient’s image and data, these happen much more frequently than is strictly necessary.

Pilots could, in the future, report in problems on a plane requiring maintenance in great detail well before arrival, while automatic telemetry can allow airlines to monitor and troubleshoot wear well before it occurs.

Boeing is optimistic about future versions of Wi-Fi acting as the data backbone on the plane advancing the possibility of services that can be delivered through on-board equipment. “We believe Wi-Fi technology is advancing at a rate quick enough, that eventually for a product like the 787, you’ll see Wi-Fi as the backbone not just of communication but of entertainment,” said Deal.

Turbulence Ahead?

Connexion’s picture sounds awfully rosy, but there are some caveats. So you may want to return to your seats and buckle in, just in case.

• Ku-band limitations

Ku-band satellites are regionally focused, which means that too many planes in a single area can oversubscribe the bandwidth that’s available on popular routes. If Connexion becomes successful, they may need to lease many more transponders, or may find a shortage of transponders in the areas they need. This can be solved with additional satellite launches – which Boeing wouldn’t pay for directly.

• Security

Connexion offers no security overlay, such as 802.1X or a private VPN. Customers must supply their own security, and it’s recommended – as with any public, open Wi-Fi network – that either all open application streams, such as POP, SMTP, and IMAP for email, be secured with encryption or that you use a VPN.

VPN service can be “rented” from companies like HotSpotVPN.com for an unlimited amount of data at a fixed monthly rate. All those interviewed found their VPN connections worked flawlessly, as did I in my test flight.

As far as security, Connexion doesn’t disclose precisely how it deals with privacy and security combined. But Schmid reported that he could not see any shares or other networks when he attempted to browse his plane’s WLAN. So it looks like the service is likely using VLANs to keep user traffic separated – a common technique used in some public hotspots.

Deal demurred when asked whether logs containing information about connections or users were stored, but referred customers to Connexion’s privacy policy which he says takes a very conservative policy in favor of users.

• Keeping it Clean

Pornography isn’t filtered out by default. “We had a working group of airlines as we were innovating the network, and one of the most spirited issues happened over what happens in an airplane cabin in the area of content,” said Deal. Connexion offers a filtering service for airlines that want it, but “it created more of a nuisance than a benefit.”

Deal said that airlines already cope with the problem of inappropriate material being displayed on laptops and portable video players and said “the advent of bringing the Internet in the cabin has not created the issue of people behaving badly.”

Nothing but Blue Sky

Tenzing, Boeing’s only real competitor, offers only a low-speed service of about 64 to 128 kbps that relies on the old domestic AirFone infrastructure over the U.S. and the satellite operator Inmarsat‘s low-speed third-generation network over water and elsewhere. Tenzing merged last year into a new company – OnAir – that is partly owned by Boeing’s rival, Airbus.

Figure 5: How Tenzing Works

(click image to enlarge)

Currently, this service – that costs $10 to $20 to view the first two kiloBytes of each message – is limited on most airlines to checking email through a Web interface to an on-board proxy server. However, Inmarsat has launched the first of two to three fourth-generation orbiters that provide 432 kbps per channel symmetrically, and can bond 1, 2, or 4 channels for a plane. Because thousands of planes already have Inmarsat avionics equipment, Tenzing’s solution requires a small investment and radio upgrade to use the newer satellites. They expect to start rolling this out in late 2005.

Inmarsat uses beam-forming transponders that allow bandwidth to be focused on small areas, thus allowing them to pinpoint access where it’s needed. But they will only have a few hundred transponders on each satellite and it’s a unique approach – which means success can also challenge Inmarsat’s ability to provide service at a high level.

Connexion appears to have packaged the right amount of speed and simplicity into their offering, providing reliability, remarkably low latency, and a consistency of service that’s starting to extend to regular routes from major airlines. And Internet service providers and roaming service aggregators have signed deals left and right with Connexion in recent months.

This all makes it likely that if you’re a corporate user and have a package already installed on your computer that you use for dial-up, hotel Internet, and hotspot use on the road, that it includes a Connexion option. Note, however, that Connexion and these partners haven’t disclosed the discounted rate. Connexion has also signed direct deals with some corporations that allow an employee to use their corporate login to gain access; billing is handled for that automatically.

It continues to be a question as to whether the billions of dollars that Boeing has reportedly poured into this endeavor will ever be fully recouped. But the division has finally moved from talking about technology to having it readily available. And the early favorable word makes it more likely that both Boeing and its rivals will be unwiring the skies even further.