Introduction

Updated 10/17/2007: Removed AppleTV 5 GHz information. Corrected troubleshooting agent info in Hands On section.

| At a Glance | |

|---|---|

| Product | Apple AirPort Extreme Base Station with Gigabit Ethernet (MB053LL/A) |

| Summary | Dual Band draft 11n router with gigabit Ethernet, print and file servers |

| Pros | • Easy to set up • Virtually no WPA2 throughput loss • Print and file servers • Gigabit Ethernet ports • Works as router or access point |

| Cons | • Doesn’t work on both 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz simultaneously • Very high WEP-enabled throughput loss • Only three LAN ports • No SPI firewall • Lacks support for port triggering |

If Apple is known for anything, it’s for elegant industrial designs. So it really comes as no surprise that Apple’s new AirPort Extreme Base Station with Gigabit Ethernet is probably the nicest looking wireless router on the market.

Although the product name is one of the longest ones on the market, it doesn’t completely describe the product’s capabilities. In addition to being a speedy router with gigabit LAN and WAN ports, the Extreme is a dual-band 802.11n Draft 2.0 wireless router. This draft specification, while not an IEEE ratified standard, is a stable draft and is the basis for the Wi-Fi Alliance’s latest certification program.

Product Tour

Figure 1: Front view of the AirPort Extreme Base Station

Measuring 6.5″ X 6.5″ X 1 3/8″, the AirPort Extreme base station is housed in a glossy white case. Unlike virtually every other wireless router on the market, the AirPort Extreme has just a single LED status indicator on the front panel. This multi-colored LED shows normal operating conditions, as well as error conditions. By default, this LED does not blink to indicate network activity, but you can change this in the admin interface.

Figure 2: Rear view of the AirPort Extreme Base Station

A glance at the rear panel of the AirPort Extreme shows that it’s quite different from other wireless routers. First, noticeably absent are the multiple external antennas that adorn competing products. Its three antennas are contained inside the base station, giving it a sleek, clean look.

Second, there are only three LAN ports—most consumer products have four. It’s important to note, however, that both the WAN port, as well as the three LAN ports, support gigabit Ethernet (but not jumbo frames). The rear panel also has a power connector jack, security lock slot, and a single USB port that can be used for printer sharing or for attachment of an external USB Drive.

Apple deserves credit for its external power supply. It’s a color-coordinated white inline brick that features a six-and-a-half-foot long white AC power cord and a 10-foot long white DC power cord. The extra length cables give you more options for placement of the base station. In addition, of course, an inline brick-type power supply doesn’t tie up multiple power outlets like many “wall wart” transformers tend to do.

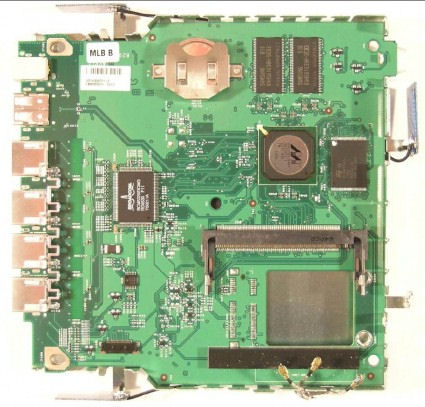

On The Inside

Figure 3: Circuit board of the AirPort Extreme Base Station

The AirPort Extreme is powered by a Marvell 88F5281 processor and a Broadcom BCM5397 gigabit switch.

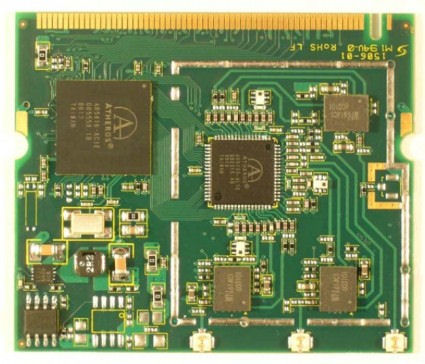

Figure 4: Mini PCI RF module

The radio in the AirPort Extreme base station uses an Atheros dual-band xSPAN chipset. With only a single radio, you have the option of operating on the 2.4 GHz or the 5 GHz band, but not on both bands simultaneously. This single band operation is probably the biggest limitation of the AirPort Extreme.

![]() See this slideshow for more construction details.

See this slideshow for more construction details.

The only other currently-available dual-band draft 11n router—Buffalo’s Nfiniti Dual Band Router—allows for simultaneous operation on both bands. With simultaneous dual band operation, you could stream your high definition video content on the 5GHz band where there’s a lot of open spectrum available for 40 MHz (channel bonded) operation, and still maintain a separate data network for email and web access in the 2.4 GHz band.

Apple has chosen not to allow 40 MHz bandwidth operation in the 2.4 GHz spectrum. While this ensures that the AirPort Extreme will be a good neighbor with legacy wireless networks, throughput in the 2.4 GHz band will be lower than in the 5 GHz band where 40 MHz operation is permitted.

Setup

Marching to the beat of a different drummer, Apple eschewed traditional web browser-based configuration found on most wireless routers in favor of their own AirPort Utility. While lacking the ubiquity of a web browser, the AirPort Utility is tailored to provide the user with a good setup experience.

Versions of the AirPort Utility for both the PC and the MAC platform are supplied on an accompanying CD. I installed both. and both versions worked, for the most part, identically.

If you drop by the Apple site and check out the reviews of the AirPort Extreme, the common thread is ease of setup. Indeed, using the AirPort Utility, the AirPort Extreme base station is quite simple to set up. You can be up and running in a matter of minutes.

When you first launch the AirPort utility, it searches for an AirPort base station. When you select the base station to configure, you either start through an eight-step wizard, or, for the more adventurous, select the Manual Configuration option.

![]() Step through the setup wizard in this slideshow

Step through the setup wizard in this slideshow

Apple did a good job in choosing which steps to include in the setup process. Too many wireless routers don’t include either setting up wireless security or the option to change the default password as part of their configuration wizards.

For the majority of users, the basic configuration will be adequate. However, others may need or want to explore some of the additional features available using the Manual Configuration option.

Across the top of the Manual configuration screen, you’ll find five top-level icons: AirPort, Internet, Printers, Disks, and Advanced.

AirPort—This top-level menu has four sub-menus:

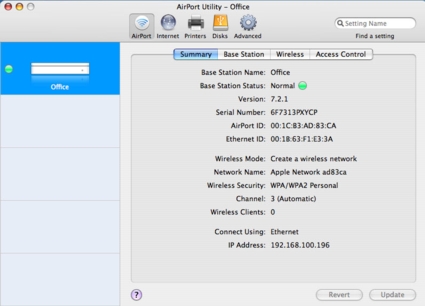

Summary provides a summary of your currently selected AirPort.

Figure 5: AirPort Utility—Manual Configuration Summary Screen

Setup – Base Station

Base Station lets you change the name/password of the base station, select a time zone and one of Apple’s three NTP time servers, enable management over the WAN port (not recommended because of security issues), enable Bonjour, and control the front panel status light. Bonjour, formerly named Rendezvous, is Apple’s implementation of ZeroConf. Intended primarily for use on local networks, Bonjour allows for the discovery of other computers, printers, and services.

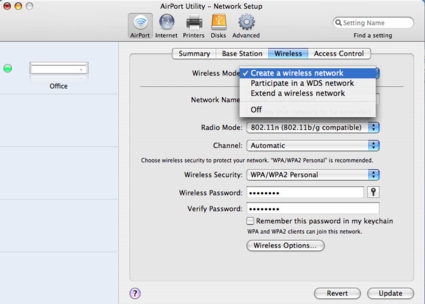

There are a number of configurable options on the Wireless menu. You can create a wireless network (default), participate in a Wireless Distribution System (WDS) network, or use the base station to extend a wireless network. WDS, a feature not normally found on Draft N products, allows for multiple access points to interconnect wirelessly without the need for all access points to have a wired backbone link.

Figure 6: Configuration of Wireless Mode

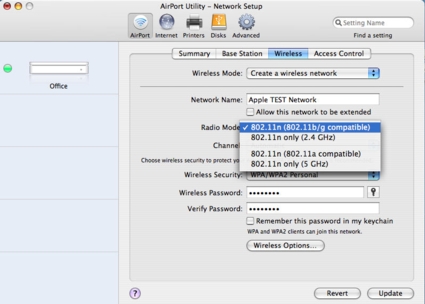

Figure 7: Configuration of the AirPort Extreme’s Radio Mode

You also can set the radio mode. For each operating band, there’s an “n only” mode that restricts access to the AirPort Extreme to Draft N compatible wireless clients. In addition, for each operating band, there is a “legacy” mode that will allow the AirPort Extreme to operate with previous generation wireless technologies. For the 2.4 GHz band, there’s interoperability with 802.11b and 802.11g clients. In the 5GHz band, there is backward compatibility with 802.11a clients.

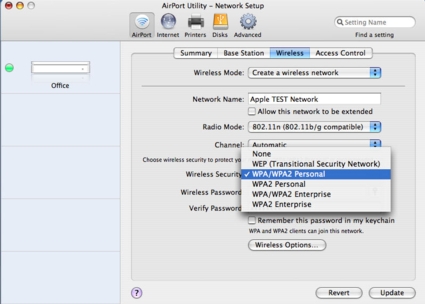

Figure 8: Configuration of the AirPort Extreme Wireless Security Settings

In the Wireless menu, you can also set or change the wireless security configuration. The AirPort Extreme, in addition to supporting WEP and WPA/WPA2 Personal, also supports authentication to an external RADIUS server through its two “Enterprise” WPA modes.

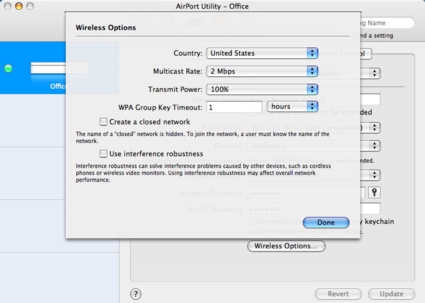

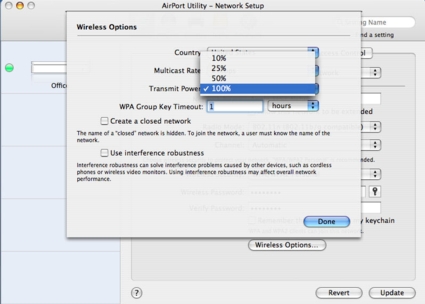

Wireless options allow you to create a “closed” network (suppress SSID broadcast), enable interference robustness which can help mitigate problems caused by other wireless devices, change the multicast rate, change WPA group key rotation time and adjust power output to 10%, 25%, 50% or leave it at the default 100 %.

Figure 9: AirPort Extreme Wireless Options

Figure 10: You can adjust the AirPort’s output power

Setup – Access Control

In the Access Control menu, you can choose either timed access based on MAC address, or enable RADIUS authentication, which requires an external RADIUS authentication server.

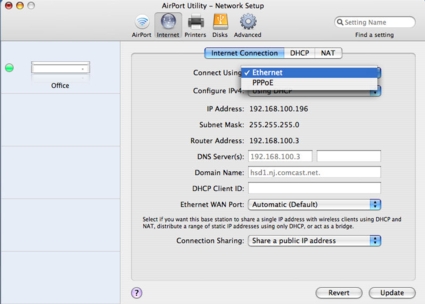

The Internet menu is a bit of a misnomer, as this menu tree lets you configure both your WAN and LAN connections.

Internet Connection lets you set up how you connect to the Internet. You can choose either Ethernet (with static or dynamic IP) or PPPoE.

Figure 11: Configuration of Internet Connection

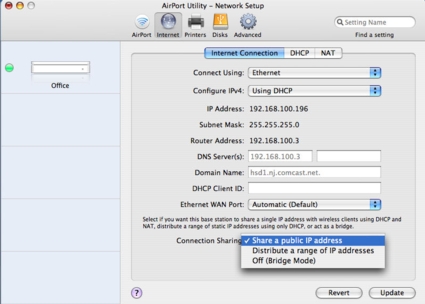

The AirPort Extreme has an interesting option under the Connection Sharing menu. In addition to the traditional sharing of a public IP address, this configuration also lets you disable routing functions, effectively converting the AirPort into an access point, as well as distribute a range of public IP addresses that may have been assigned to you by your ISP.

Figure 12: Connection Sharing Configuration

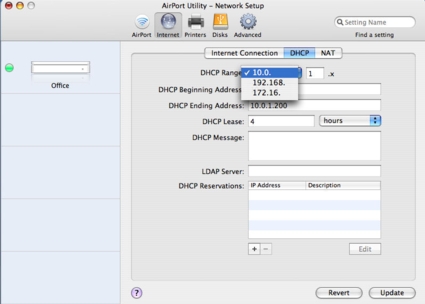

Setup – DHCP

The DHCP menu lets you set the DHCP range of addresses, the DHCP lease time (default—4 hours) define an LDAP server, and set up DHCP reservations. Though you can set up DHCP reservations, it’s more difficult to do, as you have to set it up manually. You can’t choose from a list of clients to populate your DHCP reservation table like you can with other routers such as the D-Link DIR655.

It’s interesting to note that this tab is also where you define your LAN address. You have a drop-down box of the three non-routable IP subnets—i.e., 10.0.0.0, 192.168.0.0, and 172.16.0.0. You don’t have any control over the subnet mask—they are all “/24s” (255.255.255.0), and the base station assigns itself the first address in the range.

Figure 13: DHCP Configuration

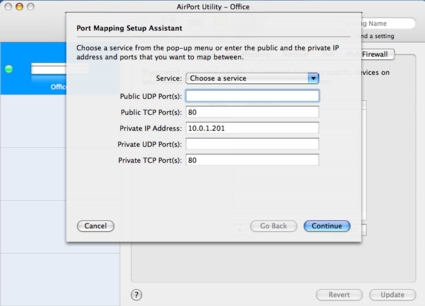

In the NAT submenu, you can enable a default host that’s exposed to the Internet (i.e., DMZ), as well as enable NAT Port Mapping Protocol. Apple’s help screen indicates that NAT-PMP is an alternative to UPnP that’s implemented in many other routers.

There is also a tab for configuring port mappings. Clicking on that tab takes you to the advanced menu and the port mapping submenu. I found it interesting that the AirPort Extreme doesn’t support port triggering, which is important to online gamers. With port triggering, an outbound packet on a “trigger” port automatically opens pre-defined inbound ports used by a particular application.

Figure 14: Configuration of Port Mapping on the AirPort Extreme

Setup – Printers

There are no submenus for the Printers section. This selection shows connected USB printers, if any, and provides the option to share the printer on the WAN port and advertise it using Bonjour.

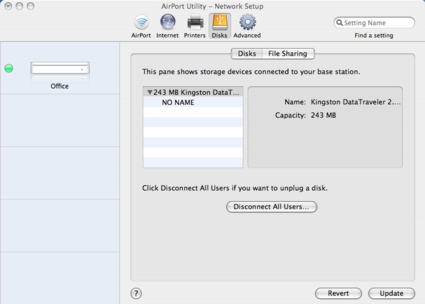

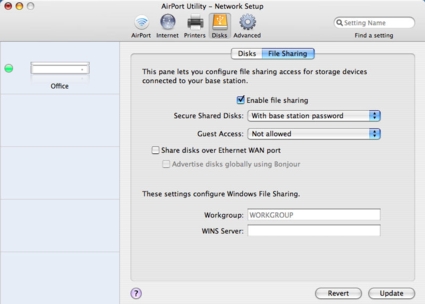

The Disks section controls access and file sharing of attached USB drives.

Figure 15: Currently connected USB drives and the disconnect button

The Disks submenu shows currently connected USB drives, with the option of disconnecting users prior to unplugging the drive.

Figure 16: File sharing submenu

The File Sharing submenu allows you to enable/disable file sharing, choose access to the disk (base station password, disk password, or user list), and set guest control. As with printer sharing, you can choose to share the disk on the WAN port and to advertise it using Bonjour.

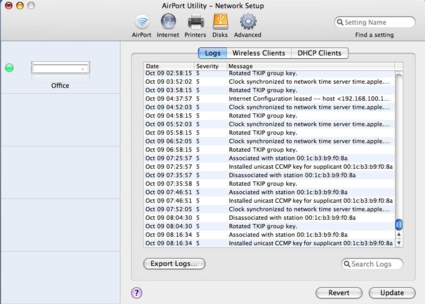

The Advanced section has a collection of advanced features that you can configure. The AirPort Extreme supports SNMP, and optionally, SNMP on the WAN port. Syslog, with eight levels of reporting, is also supported for log reporting. A second-level menu lets you view and export the AirPort’s log; view attached wireless clients, along with their signal, noise and rate information; and view a DHCP client list.

Figure 17: AirPort Extreme’s log page.

You can also see signal strength, noise and rate information for attached clients.

Figure 18: AirPort Extreme shows signal strength, noise, and rate information for attached clients.

Other Advanced submenus include Bonjour, which allows you to configure Bonjour to allow computers on the Internet to connect to the base station, IPV6, which allows configuration of IPV6 in Tunnel mode, Link-local or node modes, and IPV6 Firewall, which provides limited configuration of the IPv6 firewall. I did not test any of the IPV6 capabilities.

Hands On

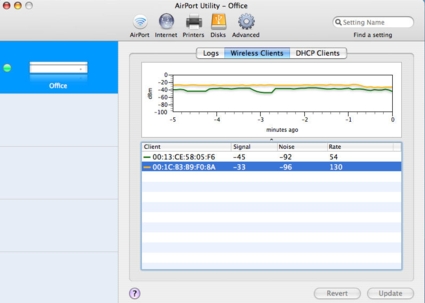

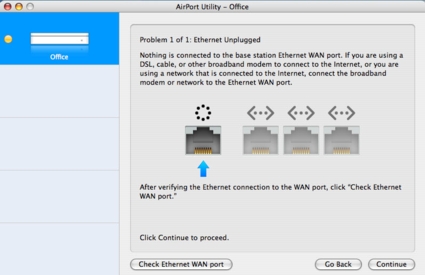

Though the menu options on the AirPort Utility are consistent between the Mac and the PC version, I did notice some differences between the two when I had the utility running on both platforms at the same time. For the Mac version, the AirPort utility has an agent that runs even when the utility isn’t open. This agent can detect certain types of problems and provides guidance for resolving the problem. To test this, I disconnected the Ethernet cable on the WAN port. Within a few seconds, a screen popped up on the Mac showing that the WAN Ethernet port was unplugged.

Figure 19: AirPort Utility Showing WAN disconnected

Note that the status light is amber and mirrors the status light on the AirPort Extreme. When I plugged the WAN Ethernet cable in again, the problem cleared and the status light returned to green. I had expected a similar diagnostic to run on the PC platform, as there is a service that runs and appears in the system tray. It didn’t. That service appears to only control preferences for automatically detecting disks plugged into the AirPort’s USB port.

Updated 10/17/2007: The troubleshooting/monitor screens will appear only on computers that have been used to configure the base station—both Windows and MacOS.

Next, I attached a USB Flash drive to the USB port on the AirPort Extreme. On the PC, a popup window appeared showing that a disk had become available on the AirPort Extreme. After typing in the password for the AirPort (my configuration choice when I set up the AirPort), the drive automatically mounted as a mapped drive.

Figure 20: Pop-up windows on the PC showing a newly attached drive on the AirPort Extreme

On the Mac, since I had previously saved the password on the key chain, the drive mounted and appeared on the desktop.

I did experience one anomaly, however. I connected an external USB drive that had multiple partitions—one formatted for Windows and the other for an EXT2 Linux partition. The drive mounted properly when attached to a PC, but the AirPort reported a disk problem and didn’t mount either partition.

If you need additional USB ports, you can plug a USB hub into the AirPort’s USB port. I tested this by plugging in a four-port hub, and then inserted two USB flash drives. Both drives were visible under the disk menu, and both mounted properly on the Mac desktop.

Routing Performance

Test and analysis by Tim Higgins

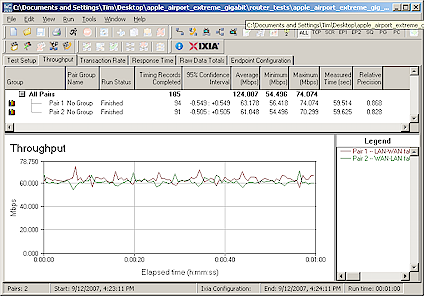

I tested routing performance using our standard router tests, using desktop machines running Windows XP SP2 for both IxChariot endpoints, since both had gigabit Ethernet LAN cards. All tests were done with the LAN client in DMZ and I had no problems getting the IxChariot tests to complete. This was probably due to the absence of SPI in the firewall, since it is SPI+NAT that usually causes problems with IxChariot test completion.

Table 1 shows around 124 Mbps of total routing throughput, which is plenty for any Internet service that the Extreme is connected to. The 128 simultaneous connections aren’t the highest I’ve seen, but indicate that use for P2P and gaming at least has a shot at being trouble free.

| Test Description | Throughput (Mbps) |

|---|---|

| WAN – LAN |

133

|

| LAN – WAN |

126

|

| Total Simultaneous |

124

|

| Maximum Simultaneous Connections | 128 |

| Firmware Version |

7.2.1

|

Table 1: Routing performance

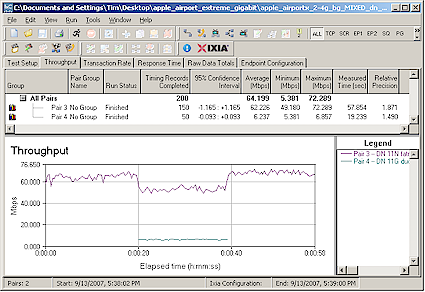

Figure 21 shows throughput variation for simultaneous up and downlink traffic, which looks pretty well-behaved. So, in all, the routing section of the Extreme looks like an average current-generation design.

Figure 21: Apple Airport Extreme simultaneous routing throughput

Wireless Performance

Test and analysis by Tim Higgins

Testing the Extreme’s wireless performance presented some unique challenges. While Ixia has a MacOS endpoint for IxChariot, it is PowerPC and not Intel-based. So I chose to install BootCamp on the top-of-the-line black MacBook that Apple sent along with the Extreme and loaded a copy of XP Pro SP2. (I actually ended up running some quick throughput tests using the PowerPC IxChariot endpoint, which seemed to produce results similar to those produced by XP.)

The router already had the latest 7.2.1 firmware and I left all factory default settings in place, except as noted.

Maximum Throughput – 2.4 GHz

To start, I ran some close range open-air IxChariot tests to look at maximum performance and throughput variation. This also provides baselines to check the Azimuth results against. As with the routing section tests, I ran all open-air wireless tests with Win XP SP2 running via BootCamp in the MacBook.

Testing was done with the router and MacBook about 10 feet apart in open air sitting in my lab with no other networks in range.

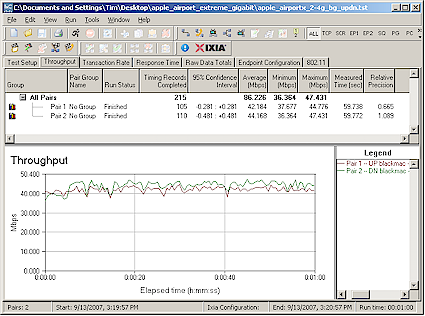

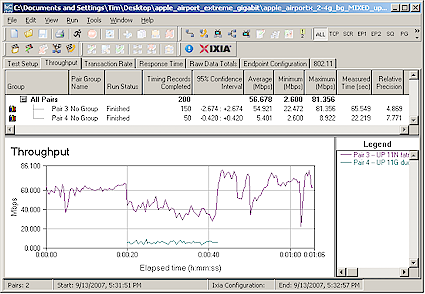

Figure 22 shows simultaneous up and downlink results in the default 2.4 GHz mode (b/g compatible), which come in at around 86 Mbps of total throughput. Running up and downlink separately yielded results of 78 and 66 Mbps respectively.

Figure 22: Up and downlink throughput – 2.4 GHz band, 20 MHz bandwidth

Since Apple has chosen to lock out 40 MHz bandwidth (channel bonded) operation in the 2.4 GHz band, I couldn’t test that mode. But I did check the “n only” mode and saw little performance difference.

Maximum Throughput – 5 GHz

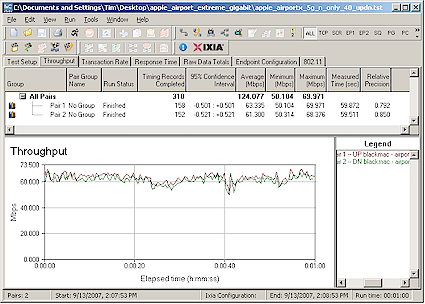

I next checked throughput in the 5 GHz band. In this band, Apple defaults to using the 40 MHz bandwidth and “11a compatible” modes, so that’s what you see in Figure 23. The total throughput of 124 Mbps is pretty impressive and better than the 103 Mbps of total up/down throughput turned in by the only other dual-band draft 11n router now available, the Buffalo WZR-AG300NH. I should note, however, that this superior performance was not reproduced in the Azimuth-based throughput vs. path loss testing. More on this shortly.

Figure 23: Up and downlink throughput – 5 GHz band, 40 MHz bandwidth

Maximum Throughput – 5GHz – more

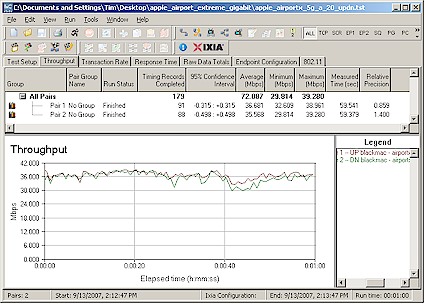

Figure 24 shows that when the Extreme is switched to its 20 MHz bandwidth mode, throughput drops to 72 Mbps, almost 20% less than the maximum 2.4 GHz band throughput.

Figure 24: Up and downlink throughput – 5 GHz band, 20 MHz bandwidth

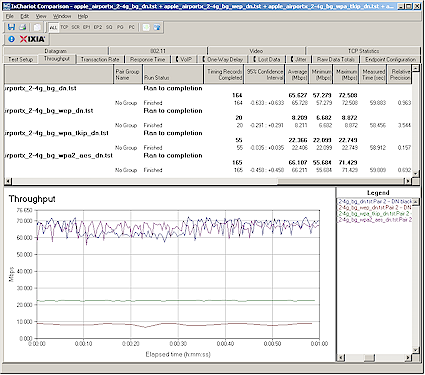

Security mode throughput

I’ve found surprisingly high throughput reduction in draft 11n products and the Extreme was no exception. Since it is based on the Atheros XSPAN chipset, I expected very high throughput loss in WEP and WPA/TKIP modes and found almost 90% and 65% loss respectively in downlink tests (Figure 25). The 90% loss is a new high (or low, depending on your perspective) and pretty shocking.

Figure 25: Security mode throughput comparison – downlink

The good news is that WPA2/AES showed no significant throughput loss in downlink. This is the best performance I’ve seen yet and should be the expected performance, since encryption hardware is built into the wireless chipset.

For uplink, the percentages move around a bit, but the relative performance of the modes remains the same. Once again, the message is, for best secured performance, you must use WPA2/AES.

Throughput vs. Path Loss

It’s my practice to test wireless routers with their recommended client cards. Since Apple doesn’t produce a companion Airport Extreme “Notebook” card for Windows machines, they sent along a top-of-the-line MacBook to fill the need.

But the Azimuth ACE 400NB Channel Emulator that is used for throughput vs. path loss testing requires the use of a Windows application on the wireless client and direct access to both router and client antenna terminals. I was able to get the Extreme opened up fine. But Apple frowned on my idea of opening up the MacBook, and after having checked out ifixit’s excellent disassembly instructions, I have to admit I wasn’t so hot on the idea, either.

I first tried to find an Atheros-based dual-band Cardbus card to match the Extreme’s wireless chipset. But no vendor has yet shipped (or even announced) such a beastie. So after my direct appeal to Atheros for an engineering sample was politely refused, I had to switch to Plan C.

For 2.4 GHz testing, I used an Atheros XSPAN based D-Link DWA-652 Notebook card—the same used for the D-Link DIR-655 testing. The card was inserted into a Fujitsu P7120 Lifebook (1.2 GHz Intel Pentium M, 504 MB) notebook running WinXP Pro SP2 with all the latest updates. I used the 6.03.85 “Draft 2.0” driver and Windows Zero Config.

For 5 GHz testing, I used the only dual-band draft 11n CardBus card available—the Buffalo WLI-CB-AG300N used to test the Buffalo Nfiniti Dual-Band Router. The card was used in the same Fujitsu notebook with its 3.0.0.13 driver and Windows Zero Config. Note that since this card uses the Marvell TopDog wireless chipset, it doesn’t necessarily represent best-case performance.

NOTE: We no longer refer to “range” in these plots, but instead use the more accurate “Path Loss”. For an explanation, see the How we Test Wireless article.

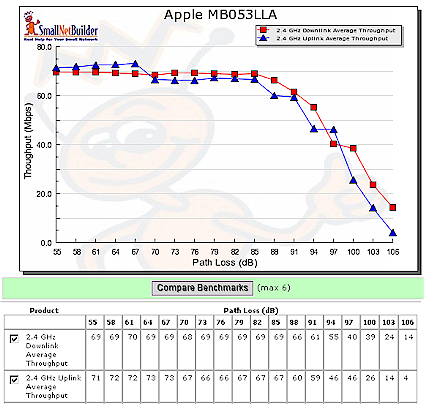

Figure 26 was generated using the Compare Benchmarks tool of our Wireless Charts and shows 2.4 GHz up and downlink performance. Performance is surprisingly similar in both directions, which has tended to not be the case with most draft 11n products.

Figure 26: Throughput vs. Path Loss – 2.4GHz

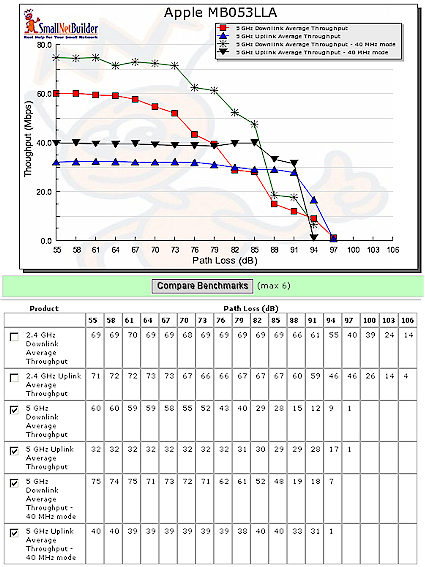

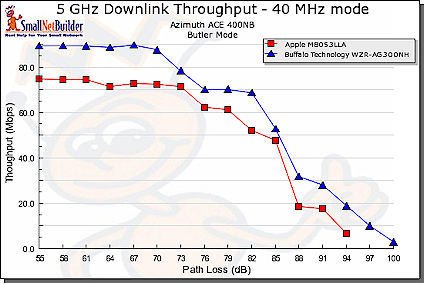

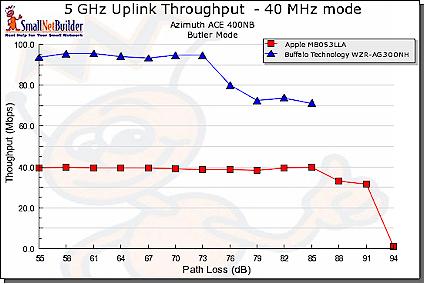

Figure 27 shows performance in the 5 GHz band, which includes both 20 and 40 MHz bandwidth modes. Here, up and downlink performance is more like what I’ve seen with other products—noticeably different. As is typical with other draft 11n products, throughput falls off more sharply when running in 40 MHz bandwidth mode.

NOTE: 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz test results can only be compared within each frequency band. The Azimuth system does not reflect the difference in signal attenuation between the bands in the mathematical models it uses.

Figure 27: Throughput vs. Path Loss – 5GHz

Throughput vs. Path Loss – Product Comparison

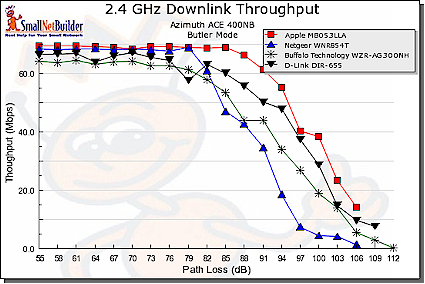

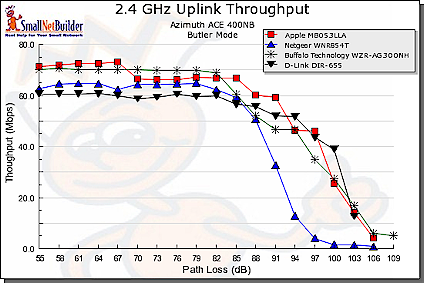

Moving on to some product-to-product performance comparison, Figures 28 and 29 pit the Extreme against the three next-best performing products that we’ve tested: The Netgear WNR854T (Marvell-based), Buffalo WZR-AG300NH dual-band (Marvell), and D-Link DIR-655 (Atheros). Note that all have gigabit WAN and LAN ports.

Since the Extreme doesn’t support 40 MHz bandwidth mode in the 2.4 GHz band, those plots show only 20 MHz bandwidth mode performance. The Extreme leads the pack for downlink, followed by the D-Link DIR-655, which is also based on Atheros XSPAN silicon.

Figure 28: Throughput vs. Path Loss product comparison – 2.4 GHz downlink

The uplink comparison is less clear, with only a clear laggard, the Marvell-based Netgear WNR854T, which falls off faster than the others.

Figure 29: Throughput vs. Path Loss product comparison – 2.4 GHz uplink

For comparison in the 5 GHz band (Figures 30 and 31), there is only the Buffalo Nfiniti dual-band, which does better than the Extreme in downlink and 40 MHz bandwidth mode.

Figure 30: Throughput vs. Path Loss product comparison – 5 GHz downlink

The last plot (Figure 31), which shows 5 GHz uplink is pretty interesting. The Buffalo quits pretty early on and doesn’t even hit the “waterfall” portion of its curve. I suspect that this is due to a link rate adjustment problem that caused the Buffalo client to disassociate, ending the test.

Figure 31: Throughput vs. Path Loss product comparison – 5 GHz downlink

The Extreme’s relatively poor showing, compared to the tests made with the MacBook, is probably due to the mix of Atheros and Marvell chipsets. While manufacturers have made advancements in interoperability, the results show that you’re still better off using “matched” products for maximum performance.

If you don’t like these comparisons, you can run your own using the Wireless Charts tools!

Mixed STAs

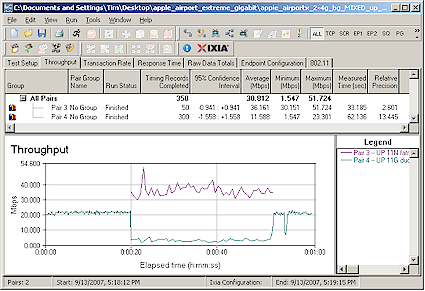

To see how the Extreme handled mixed draft 11n and 11g clients, I set up a second notebook with a Linksys WPC54G V3 11b/g card (Broadcom chipset). Both it and the MacBook were associated with the Extreme, which was set to its default 2.4 GHz “b/g compatible” mode with 20 MHz bandwidth. I then ran two IxChariot throughput.scr streams, alternating the STA that got on the air first.

Figure 32 shows how uplink throughput was shared when the 11n pair started first, while Figure 33 shows the 11g pair starting first.

Figure 32: Mixed 11n, 11g STAs – Uplink, N starts first

The results follow the pattern that I’ve seen with other draft 11n products,i.e. the 11g STA gets knocked down to 11b speeds. In this case the 11g throughput is knocked down to about 6 Mbps from its normal 22 Mbps or so, or about 75%. The 11n pair’s throughput hit is only about 33%.

Figure 33: Mixed 11n, 11g STAs – Uplink, G starts first

I also ran these tests in downlink (Figure 34) which shows a smaller throughput hit for the 11n STA (about 20%), but about the same for the 11g.

Figure 34: Mixed 11n, 11g STAs – Downlink, N starts first

That about wraps up the wireless testing. I didn’t run any Legacy Neighbor / CCA tests because the 40 MHz bandwidth mode is locked out in 2.4 GHz.

Final Thoughts

By Craig Ellison and Tim Higgins

Hands down, the Apple AirPort Extreme is the nicest looking wireless router on the market. It has a clean, sleek design, white housing, and a lack of external antennas; these features allow it to look great anywhere you install it.

While looks are nice, it is features and performance that sell wireless routers. But the Extreme is no laggard in both performance categories. It ranks in the top 5 in our Router Charts and at the top of our Wireless Charts for average total throughput in the 2.4 GHz band. And we’re willing to bet that had we been able to perform our 5 GHz throughput vs. path loss testing with an Atheros XSPAN-based client, that it would have been at the top of that chart, too.

Its main wireless weakness is high throughput loss when running either WEP or WPA/TKIP wireless security. But this seems to be a common weakness among the current crop of draft 11n products.

Turning back to the positives, we like that the AirPort Extreme features gigabit Ethernet ports, can easily be configured as a router or an access point and can join a WDS network or function as a repeater. With its support for WPA/2 enterprise (RADIUS), it can also fit into a corporate environment. And the Extreme’s inclusion of both print and basic file servers adds to its appeal.

But the Extreme isn’t perfect. Though it is a dual band router, it’s limited by a single radio that restricts it to operating on one band at a time. This tradeoff was probably made to keep cost down, but with draft 11n chipset prices dropping, we’re not sure this was the right choice. Although the Buffalo Nfiiniti is currently the only dual-band competition, the price difference has dropped to $50-$70, vs the $100+ that it was back when the Buffalo first hit the market. And with more simultaneous dual-band products due to hit the market before the end of the year, the either/or choice forced upon users by the Extreme could cost it some market share.

We were also surprised at the lack of some features that are commonly found on significantly less expensive devices. For example, the Extreme lacks an SPI (stateful packet inspection) firewall and relies only on NAT for firewall protection. SPI firewalls allow outgoing packets, but only permit inbound packets if they are part of an established connection. While the importance of this feature may be debatable, it is curious that Apple omitted it, since pretty much every other consumer router sports a NAT+SPI firewall.

Turning to more important omissions, the Extreme doesn’t support port triggering—a feature important for the online gaming community. And while it does support WMM for prioritizing multimedia on the wireless network, it lacks QoS controls on both the wired and wireless networks.

We would also like to have seen the Extreme implement Dynamic DNS (DDNS). Bonjour advertisements on the WAN port may someday fill that need, as ISPs and DDNS providers update their environments to accept Bonjour resource updates. But DDNS is the way to go today, if you need to remotely access services on your LAN.

Finally, the use of application instead of browser-based administration seems to be another odd choice. To its credit, Apple has done an admirable job at providing (almost) equal admin function access to both MacOS and Windows users (which is more than can be said of most consumer networking products). But for a company whose OS is open source based, the choice to exclude those users seems to be an odd one.

All things considered, however, the AirPort Extreme is a cost-effective high-performance dual band draft 11n router that will work well in both a Mac and a PC environment. Despite its lack of simultaneous dual band operation and browser-based administration, it’s definitely the way to go if you need dual-band draft 11n today.